- Hill Heat

- Posts

- The Walter J. McCarthy Jr., Concluded

The Walter J. McCarthy Jr., Concluded

Part Two of a climate policy advocate's personal reflections on Duluth, an American city at the intersection of climate and industrial policy

A brief note on the news in Washington: At 2:18 am, while Sen. Tina Smith (D-Minn.) was hospitalized overnight, Senate Republicans forced through the passage of H.R. 4, a $9 billion rescissions package that retroactively authorizes Trump’s unconstitutional elimination of international programs. The legislation kills the Corporation of Public Broadcasting, U.S.A.I.D., the U.S. Institute of Peace, and other organizations, and withdraws the U.S. from international efforts including the Montreal Protocol, World Health Organization, and the Clean Technology Fund. Final House passage is expected within 24 hours.

The conclusion of The Walter J. McCarthy, Jr., climate policy advocate Jordan Haedtler’s personal reflections on Duluth, an American city at the intersection of climate and industrial policy.

Continued from Part One, in which Jordan Haedtler recounted his family’s legacy in the Twin Ports region, where he moved as President Biden fought to enact the Build Back Better agenda.

Biden was right to try to bring climate and industrial policy together. Addressing the climate crisis necessitates economic transformation on the scale of what it took to fight the Great Depression and fascism during World War II.

The tech tycoons

But this New Deal nostalgia is anathema to the worldview of many who are now in power, especially the Silicon Valley futurists who recently joined Donald Trump on a deal-making excursion to Saudi Arabia. The dangerous worldviews of these futurists are meticulously unpacked in Adam Becker’s book More Everything Forever. Becker summarizes the common threads between effective altruism and other common Silicon Valley philosophies:

“Social problems and political problems— like the problems created by tech companies themselves— are dismissed as irrelevant or unimportant when compared to more urgent problems, like avoiding the creation of an improperly aligned AI or the plight of the hypothetical unborn quadrillions of humans…”

Becker describes Silicon Valley futurists’ steadfast belief that new technology will save us. “I think once we have a really powerful superintelligence, addressing climate change will not be particularly difficult for a system like that,” OpenAI CEO Sam Altman has said. Altman has acknowledged that “AI is going to need a lot of energy.” His climate solution is characterized by Becker as essentially “solving global warming by asking a nonexistent and ill-defined [Artificial General intelligence] for three wishes.” There is enormous contrast between the New Deal world of tactile production, still so proximate in Duluth, and the vision of tech tycoons who hold AI as a solution to rather than a driver of the climate crisis.

This view extends well beyond Altman and the other tech giants who witnessed Trump’s inauguration. Liberal effective-altruists Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson have been promoting their book Abundance, which purports to support a vision for how large-scale decarbonization can be achieved by streamlining regulation. The book has been called an “embrace of Silicon Valley’s vision for America” by critics. Like many of their Silicon Valley patrons and peers, Klein and Thompson “gush about AI’s potential,” often implying it could serve as a climate solution.

I am all too familiar with the worldview, having grown up in Mountain View, the San Francisco Bay area suburb that now serves as Google’s headquarters. More Everything Forever describes a mindset that I’ve encountered in many interactions with Silicon Valley techies. Most are acutely aware of technological dangers. In fact, they spend their personal lives fretting about and conversing endlessly about the existential threats from things like AI. Yet they dedicate their professional lives to heedlessly pushing ahead, convinced that the solution to technological dangers lies in more technology.

Grandpa Mac seemed to carry similar contradictions and scruples. He was an obsessive student of the Atomic Age’s triumphs and perils, and his home was filled with histories of the Manhattan Project and biographies of Winston Churchill. When he died, I inherited a small radio from him, onto which he’d appended a scribbled note. He’d used the radio while at work during the thirteen days of the Cuban Missile Crisis, periodically switching it on to learn “whether our world was coming to an end.”

Grandpa Mac shed a tear when he saw news of the Fukushima nuclear accident in 2011, pained by another setback in his lifelong quest for nuclear safety. Today though, the barriers to nuclear energy have less to do with safety concerns and more to do with the financing of building new plants. Nuclear energy simply hasn’t proven reliable or cheap enough for long-term financing to materialize. “We could ‘solve’ all ‘regulatory and permitting’ issues for nuclear tomorrow and not one new plant would get ordered or built,” one of the chief architects of Biden’s industrial policy recently said.

Future generations simply don’t have the 20 years that it took for Mac to oversee the completion of Fermi II. Small modular reactors have raised funding, but their potential is still theoretical. The Biden administration’s promotion of one small modular reactor touted clean energy benefits, but that language was replaced by a Trump press release highlighting how the project would establish “America’s energy dominance to power artificial intelligence.”

For the time being, the surest best is substantial clean energy deployment of the type supported by the IRA. But Trump’s election short-circuited the IRA’s promise. Now, the unchecked growth of AI, and the related thirst for more energy by Big Tech companies, is throwing another wrinkle in the clean energy transition, forcing reconsideration even of nuclear facilities that had seemingly proven to be financially inviable. Microsoft announced a deal that will reopen the Three Mile Island plant in 2028.

Nowadays, Detroit Edison is called DTE and its CEO serves as the president of the American Gas Association. Gas boosters are excited about AI, which has been called the “savior” of the gas industry. After Michigan lawmakers passed a 100% clean energy law in 2023, Big Tech lobbied for a major incentive package to encourage development of data centers in the state. The incentives risk taking energy usage rates over off-ramps that might free DTE from complying with Michigan’s 100% clean electricity requirements. Amendments were drafted to clarify that the new data centers must rely mostly on renewable energy, but DTE was part of the corporate lobbying campaign to block inclusion of those amendments.

Duluth’s political inversion at the “Point of Rocks”

A jumbled “Point of Rocks” still divides east and west Duluth. Art Baum wrote that the Point of Rocks was where the “main personality split in Duluth occurs… West of this point of rocks Duluth is politically left, east of it is politically right.” The class dynamics Baum noted in 1949 remain the same, with more wealth in the east than the west, but the political dynamics have inverted, reflecting the national drift of working-class voters away from Democrats and toward more reactionary candidates.

Duluth’s longtime congressman, the late Jim Oberstar, typified this inversion. For decades, Oberstar represented a large congressional district that stretched out from Duluth across the then reliably blue Iron Range. He was a dying breed of Democrat, holding socially conservative and economically liberal views, and pressing the cause of the New Deal consensus throughout a period when Congress was much more inclined to support big finance and outsourcing. Swimming against this tide, Oberstar steered federal dollars toward infrastructure projects as chairman of the House Transportation Committee. Consequently, a Great Lakes ship and an airport terminal bear his name today.

The Great Lakes freighter named after Duluth’s longtime DFL congressman, who won many elections to Congress with voters that Democrats struggle to win today.

In 2010, Oberstar lost re-election during the Tea Party wave. Two years later, the Democratic-Farmer-Labor (DFL) party was able to win his congressional seat back by bringing a former Mondale staffer and congressman named Rick Nolan out of retirement. When Nolan passed away shortly before the 2024 election, his obituary highlighted his steadfast support for labor, mining, and funding for the “Soo Locks” in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (UP). In 2016, the district swung heavily toward Trump, and Nolan managed to win his final term only by outperforming Hillary Clinton by 16 points, affirming the long and pronounced lurch of working class Iron Range voters away from their traditional support for the DFL.

Since 2019, Duluth’s congressional district has been held by right-wing MAGA congressman Pete Stauber, whose main cause in Congress has been repealing environmental safeguards against mining in the Boundary Waters. Duluth itself remains largely supportive of the DFL, and most Duluthians routinely vote for Stauber’s opponents. In local elections for mayor and other offices, the city’s more affluent, eastern portions mostly support more progressive candidates, while the less moneyed western neighborhoods tend to vote for less progressive ones.

As this class inversion has unfolded nationally, an array of Great Lakes port cities that once pinned their mid-century economic dreams on the Seaway now sit at the fulcrum of all the major questions swirling around our climate and our democracy. Trump clinched his 2024 victory in Pennsylvania by carrying Erie County, often considered a bellwether. Trump also carried Michigan, where Republican state representative Karl Bohnak helped his party flip the state House by issuing misleading criticisms of Rep. Jenn Hill’s support for the 2023 clean energy law. Hill represented the ore shipping city of Marquette. She was the last Democratic legislator from the UP, which decades ago had remained blue even as the rest of the state went for Ronald Reagan.

Trump’s big margins with working class voters enabled him to win Wisconsin, though Kamala Harris improved on Biden’s 2020 performance in several communities bordering Lakes Superior and Michigan, including Sturgeon Bay, where the Big Mac was constructed. After Ohio’s rightward swing finally caught up with in 2024, Democratic Senator Sherrod Brown used his farewell address to call attention to a lapel pin given to him by steelworkers in Lorain, the Lake Erie town where many other lake freighters were built.

You can see a way in which Duluth’s next counterpunch at circumstances and events lies through some combination of Minnesota’s affection for public investment and an embrace of the city’s relevance to climate policy and industrial renewal.

But the likelihood of Great Lakes cities powering a comeback through an embrace of green industrial policy now seems more distant. Trump’s tariffs have created uncertainty for Duluth’s shipping sector, and the manufacturing renaissance appears to be on hold. A recent story about federal cuts to a program that helps Minnesota’s small manufacturers noted that the program “will shift to a focus on emerging technologies like artificial intelligence.” Trump had opposed the acquisition of US Steel as a candidate, but he flipped upon returning to the White House. In a Truth Social post, Trump endorsed the Nippon Steel deal and the extension of the polluting Gary Steel blast furnace that comes with it.

Trump reverses Biden’s climate and industrial policy

One of Trump’s earliest moves was to illegally rescind the IRA’s greenhouse gas reduction fund that supported those green banks I was working on. Trump also shuttered federal support for NASA’s climate science program, displacing its leader James Hansen, who famously testified to Congress shortly after I was born.

In less than a third of the time that it took for Joe Manchin to whittle Biden’s Build Back Better proposal down into the IRA, Trump worked with Republicans in Congress to effectively repeal the IRA. The new law is projected to have a devastating impact on the economy. Roughly a dozen congressional Republicans had voiced support for the IRA’s clean energy and EV tax credits, but they soon caved in exchange for tilting the IRA repeal bill even more generously toward the wealthy. Trump’s IRA repeal contained many fossil fuel giveaways, including provisions to open up four million new acres of federal land to coal leasing, and a subsidy for foreign companies to use this coal in steel production.

Meanwhile, those university grants to research green steel have been held in suspense. At a recent town hall discussing federal cuts, Duluthians working at an EPA water-testing facility described fears about losing their jobs. Another person who works with NOAA to conduct weather forecasting on Lake Superior also spoke out.

Final reflections

“What happened last night was that the cord that stretched back to FDR snapped,” climate writer Bill McKibben wrote on the morning after the 2024 election.

In my grief, my thoughts turned to friends and family members that I had lost during the Biden years. They had died hoping that the dark chapter of Trump’s presidency had been a blip. In one of our final conversations, Grammy pleaded with me to assure her that Trump would not come back. I thought about the news surrounding me. Attempts to prosecute Trump for his crimes were being slow-walked. Senator Manchin was blocking HR 1, Democrats’ urgent package of campaign finance and pro-democracy reforms. I stammered in my response, unable to confidently offer her that assurance.

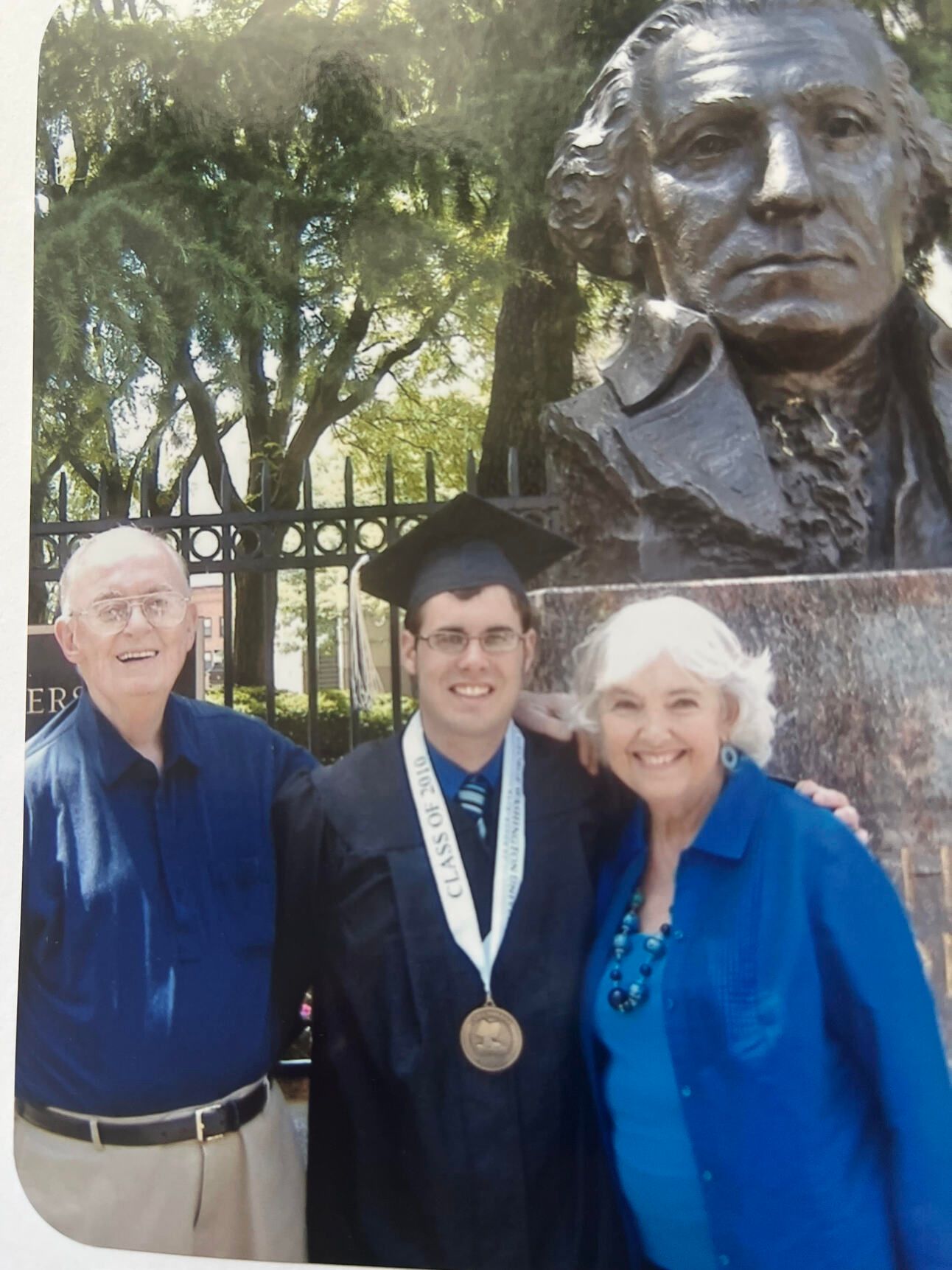

Grammy and Grandpa Mac with me at my college graduation.

As for Grandpa Mac, it’s impossible to say exactly what he would have thought about our present set of energy and political realities. He was an honest and decent man, and I am quite sure he would be disgusted by Trump’s lies and crimes. I wish I could ask him now whether he thinks the term “clean coal”— a misnomer he once used to refer to MERC’s lower sulfur coal— should finally be dispensed with. He expressed misgivings about voting for Reagan in the 1980s, though I don’t know if he ever fully rejected the business paradigm of “shareholder primacy” that formed the backdrop for Reagan’s presidency. By the end of his life, Mac was a moderate Democrat. He was a fan of the documentary Who Killed the Electric Car, which featured interviews with his old friend Stan Ovshinsky. My best guess is that he would be encouraged that clean energy is now cheaper than fossil fuels and that the EV market is picking up. I suspect that he would be a proponent of the “Prius economy” that Biden sought to create, and that he’d be bullish about nuclear’s role in that economic future.

I think Grandpa Mac probably would have been happy to see the Big Mac’s purpose evolve alongside the economy itself. Since moving to Duluth, I had placed hopes in an article I read suggesting that Great Lakes vessels could be converted for use primarily in transporting wind energy components. This speculation has not yet come to fruition. Since Trump famously hates wind energy, it now seems less likely that it will.

The cord to my grandparents’ generation has snapped. And yet, every couple weeks, I trek down to Duluth’s harbor to watch the Big Mac motor under the Lift Bridge, carrying another massive shipload of coal. Until that purpose changes, I realize that this ship, and all the wistful memories that it elicits for me, is better off being decommissioned.

This unique essay is made available for free to the public thanks to our paid subscribers. Join their ranks today and grow the movement:

Reply