- Hill Heat

- Posts

- The Walter J. McCarthy Jr., Part One

The Walter J. McCarthy Jr., Part One

Part One of a climate policy advocate's personal reflections on Duluth, an American city at the intersection of climate and industrial policy

A brief note on the news in Washington: Republicans in Congress are speeding to pass Trump’s Rescission Act, H.R. 4, to permanently kill the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, U.S.A.I.D., the U.S. Institute for Peace, and almost all U.S. foreign aid, pulling the U.S. out of the Clean Technology Fund, the Montreal Protocol, the World Health Organization, and UNICEF. The first key Senate vote succeeded 51-50.

Today, activists with Free DC are lobbying the Senate to reject the racist climate denier Jeanine Pirro as D.C. U.S. Attorney. Sen. Thom Tillis (R-N.C.), who pledged not to vote for supporters of the January 6th assault, is planning to vote for Pirro, a supporter of the January 6th assault.

On Thursday, July 17th, Good Trouble Lives On across the nation. In Washington, D.C., activists are meeting at the Union Station encampment at 10 am to lobby Congress before a mass rally at Franklin Park at 5:30 pm.

Please enjoy the first half of The Walter J. McCarthy Jr., climate policy advocate Jordan Haedtler’s personal reflections on Duluth, an American city at the intersection of climate and industrial policy.

It is August, 2021.

Flying out of DCA on my way to Minnesota, I grit my teeth at the news chyrons’ stories about New Jersey Congressman Josh Gottheimer’s “Unbreakable Nine.” Gottheimer had formed a caucus of corporate Democrats to throw more wrinkles in the discussions over President Biden’s Build Back Better package. For months, I had toiled on the package as a congressional staffer, inserting proposals for financing infrastructure investments and reforming flood insurance into interminable negotiations.

Congressional leaders had arrived at their August recess without breaking an impasse with Senator Joe Manchin, the West Virginia coal scion standing in the way of any meaningful attempt to address the climate crisis.

The negotiations had an air of desperation to them. In 2020, the pandemic, its economic fallout, and the ever-intensifying effects of fossil fuel pollution had converged. At one point, my father-in-law called to describe how his move to Eugene, Oregon had been obstructed by thick clouds of wildfire smoke. At least the pandemic had equipped him with masks that blunted that impact, he told us.

The election results that November produced the narrowest opportunity to address these problems. Yet weeks of work through the sweltering DC heat yielded little progress, as Manchin and Gottheimer refused to allow anything ambitious to move forward.

Eager to escape this environment, my partner Sarah and I scheduled a vacation in Minnesota’s Boundary Waters.

Before leaving, I called my grandmother, Linda McCarthy, then in the final weeks of her life. “If you go to Duluth,” she told me, “look up the shipping schedules. You may be able to see the ‘Big Mac’ come in.”

The Big Mac was the Walter J. McCarthy Jr., a 1,000-foot Great Lakes freight ship named for Grammy’s late husband, who I had known affectionately as Grandpa Mac.

My vague sense of Duluth was that it was like most post-industrial Midwestern cities I had visited: bleak, cold, and depressed, its best days behind it. But as we drove down Walter F. Mondale Drive, we were struck by the expansive view before us, a shimmering Lake Superior laid out on the horizon.

The Big Mac was delayed coming in, so we spent some time wandering around. We found the city’s look to be beautiful but jarring, with spectacular natural features juxtaposed against the stark infrastructure necessary to support extractive industries. Downtown was also a confusion of abandoned storefronts nestled among historic architectural treasures. We walked past old Central High School with its stately clocktower, and the St. Louis County Courthouse, a notable example of famed architect Daniel Burnham’s City Beautiful movement. Eastward along the lake, through a lovely rose garden is a statue of banking titan Jay Cooke that unironically deploys the word financier as an honorific.

Around 11 pm, the Big Mac finally floated past the lighthouses that stand at the end of the harbor, projecting radiant shades of red and green into the great expanse of Superior. Even at that late hour, a big crowd had formed to watch. I felt a twinge of pride. “This is the Walter J. McCarthy Jr.,” one tourist glanced up from his phone to explain. As the ship powered its way underneath Duluth’s majestic Aerial Lift Bridge, I recorded a video of the scene and sent it to Grammy. “Look who I found,” I texted. She was delighted.

Tourists watch as the Walter J. McCarthy Jr. arrives in Duluth

Since the St. Lawrence Seaway opened in 1959, Duluth and Superior, Wisconsin— the neighboring harbor town across the St. Louis Bay— have served as the world’s furthest inland ports accessible to ocean-going vessels. Without the Twin Ports’ silos, railroads, and ore docks, the vast mining resources of Minnesota’s Iron Range, farms of the Midwest, and coal mines of Montana and Wyoming would have no economic outlet.

Today, Duluth sits at the intersection of climate and industrial policy. Its harbor deals with all of the major pieces of a decarbonization puzzle that is still being solved. Over 560 million tons of coal have been shipped through the Great Lakes since the Midwest Energy Resources Company (MERC) terminal began operations in 1976. Meanwhile, at Clure Public Marine Terminal, wind turbine blades have been shipped from Duluth since 2006.

In an age of seamless, faceless Amazon package deliveries, it is easy to forget how much of our economy still depends on the reliable and efficient transport of raw commodities— limestone for producing cement, iron ore and coke pellets for making steel, beet pulp pellets for grazing livestock, coal for powering homes and businesses. It is an often overlooked fact of everyday life, despite the pandemic’s harsh reminders about supply chain disruptions, and the quadrennial pledges from presidential candidates to bring back American manufacturing.

Grammy (Linda McCarthy) and Grandpa Mac in front of the “Big Mac” shortly after it was re-named.

A few words on Grandpa Mac

In 1990, Grandpa Mac retired as CEO of Michigan’s most powerful investor-owned utility, Detroit Edison, which honored him by arranging to re-name a lake freighter called the Belle River. Grammy and Grandpa Mac moved to California, but the highlight of every summer during their retirement years was a return to the Great Lakes to spend several weeks on the “Big Mac.” Their tours usually began in Duluth.

Grammy and Grandpa Mac were married in May 1988, just one month after I was born. Mac was nearing retirement at the helm of Detroit Edison. That was the same year climate scientist James Hansen raised the political salience of climate change through his legendary congressional testimony, issued on a scorching hot day on Capitol Hill. A couple decades later, I had just begun working in climate politics when Mac shared his memories with me about being briefed about climate science alongside other utility executives during the 1980s. He lamented that more progress had not been made.

After retiring, Mac served on the board of Energy Conversion Development, a renewable energy company founded by his engineering buddy Stan Ovshinsky. But his preferred climate solution was greater reliance on nuclear energy. One of his crowning achievements as CEO had also occurred in that eventful year of 1988, when Detroit Edison opened the Fermi II nuclear power plant along the shores of Lake Erie. He believed passionately in safe nuclear energy, chairing the Institute of Nuclear Power Operators, which was formed after the Three Mile Island incident, and later helping to found a global organization dedicated to stronger nuclear safety standards.

Fermi II’s predecessor had been one of the first nuclear reactors to begin operating anywhere. In many ways, Mac McCarthy’s career was defined by his deft management of a partial core meltdown at Fermi I in 1966. As a teenager, I had read We Almost Lost Detroit, a detailed account of that incident. I felt a mixture of amusement and horror at the book’s portrayal of my sweet grandfather as a “cigar chewing,” “swashbuckling” engineer, wholeheartedly devoted to pressing forward with nuclear energy development despite the risks. Detroit Edison commissioned Mac to review a rebuttal to the book, titled simply We Did Not Almost Lose Detroit.

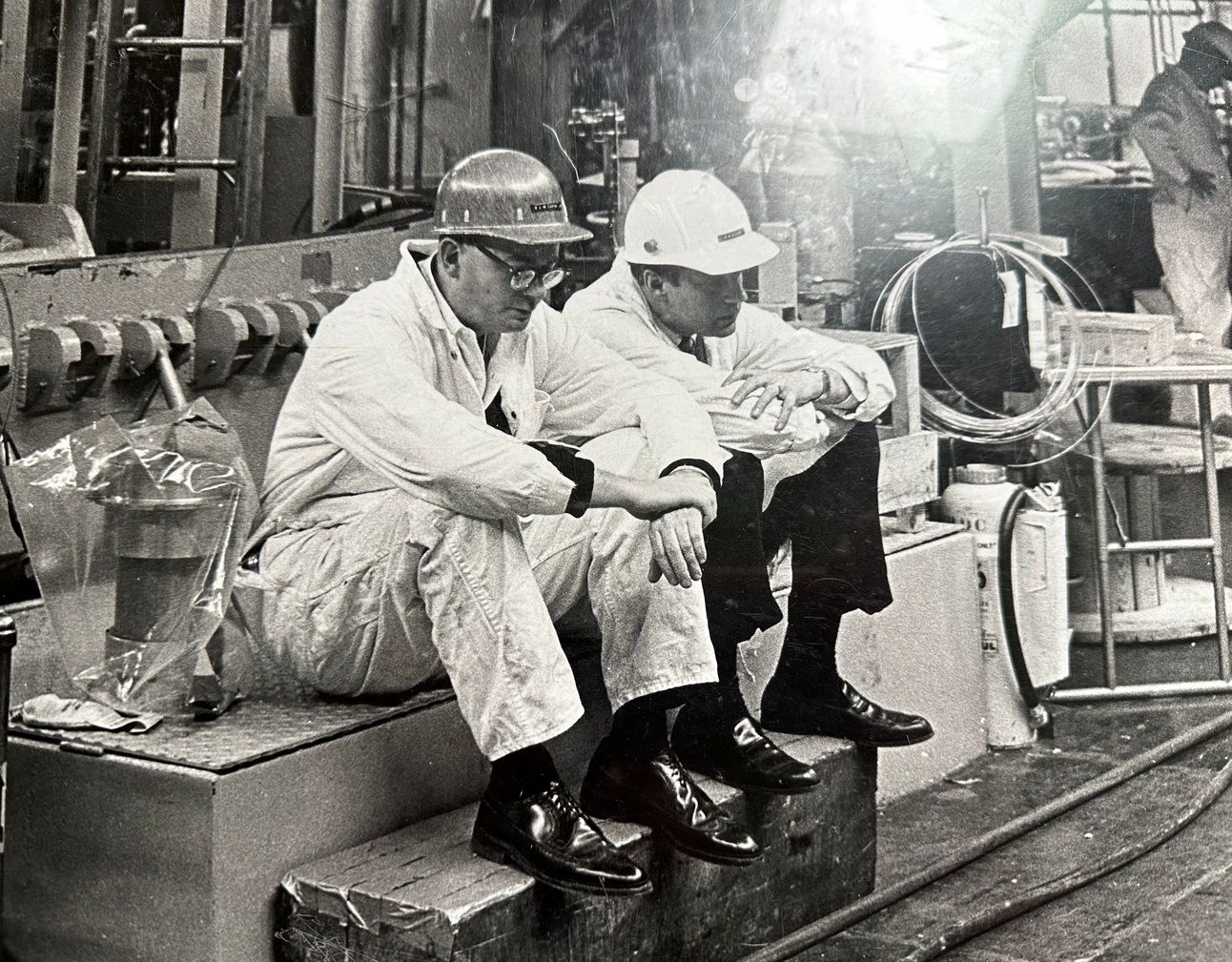

Mac McCarthy during the 1966 partial core meltdown at Fermi I.

The early chapters of We Almost Lost Detroit dig into the passage of the Price-Anderson Act, a 1957 law that resolved insurance companies’ nervousness around the nuclear industry by clarifying that the federal government would step in to pay liabilities above $13 billion when things go wrong. According to the book, Mac— “a firm believer that business is business”— thought the public supported nuclear energy, and should therefore foot the bill for insurance.

One study estimated $30 billion in public damages had the Fermi I meltdown grown more serious, and so the incident further complicated the financing of nuclear energy. In detailing the costs of new reactor developments, University of Washington scholar Sheldon Novick noted that “it is puzzling that the scientists and the resources of the United States have not been directed toward developing a less hazardous energy source.” Novick had been the first to use the term “The China Syndrome” to describe a theoretically catastrophic nuclear meltdown scenario. The fictional concept lent its name to a 1979 film, which Mac never totally forgave Jane Fonda for starring in. But The China Syndrome’s release coincided with a very real partial meltdown at Three Mile Island, spoiling the public appetite for Mac’s dream of nuclear energy expansion.

In 1982, with Mac as CEO, Detroit Edison left its mark on Duluth by acquiring MERC’s coal shipping terminal. Soon after Mac made MERC a wholly owned subsidiary of Detroit Edison, coal from the Powder River Basin grew significantly as a share of the Twin Harbors’ suite of commodity offerings. Just a few years earlier, the Big Mac had been designed as a collier meant to carry large coal shipments to Detroit Edison power plants. When the ship launched in 1977, its coal delivery from MERC set a new Great Lakes coal cargo record.

The passage of the Clean Air Act in the 1970s made the lower sulphuric content of western coal more attractive. In the 1990s, newly enacted Clean Air Act amendments prompted the expansion of the terminal, and MERC processed and shipped more western, low-sulfur coal to power plants throughout the Great Lakes region. By the early 2000s, coal was the Twin Ports’ largest export.

Midwest Energy Resources Company’s terminal in Superior, Wisc. MERC has been a wholly owned subsidiary of DTE since 1982.

“Climate proof Duluth”

In August 2022, a year after my first visit to Duluth, Senator Manchin finally allowed a scaled-down infrastructure bill to become law, and those lengthy negotiations finally culminated in the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). I wasn’t really in a mood to celebrate. By the time Joe Biden signed the IRA, I had left the dysfunction of Congress for a new job consulting on climate policy at the state level.

Still, I saw great potential in the IRA to help integrate climate and industrial policy. The major focus of Biden’s industrial policy was to develop the technologies necessary to address climate change here in the United States, and then to keep those technologies here by revitalizing the domestic manufacturing sector.

Unmoored from DC, Sarah and I took an itinerant year on the road. We added Duluth to our list of cities to spend some extended time in. Friends called our attention to stories about a phenomenon reportedly taking place in the city. The New York Times had recently run a story about hip California surfers trading the fires and storms of the Pacific coast for the intense novelty of surfing amidst the gales that come to the Great Lakes every November.

Major coverage of Duluth and climate began in 2019, when Times reporters were present to watch Harvard professor Jesse Keenan deliver a lecture called “Destination Duluth.” Keenan emphasized that Duluth sat on the edge of twenty percent of the world’s fresh water, and recommended the city rebrand itself as “Climate Proof,” to attract new residents after decades of economic stagnation.

Wildfire smoke overwhelms an industrial view of the harbor in “Climate Proof Duluth.”

CNN, PBS, and even the Daily Show have showcased Duluth in a multitude of segments about the concept of climate havens. Yet for all the media figures who have flocked to “climate proof Duluth” for trend pieces, most have missed a crucial detail: many of Duluth’s core industries are actively exacerbating the climate crisis. For all its climate resilient features, the Twin Ports are also home to an oil refinery, the sprawling coal export terminal operated by MERC, iron ore for energy intensive steel production, and limestone for carbon intensive cement production.

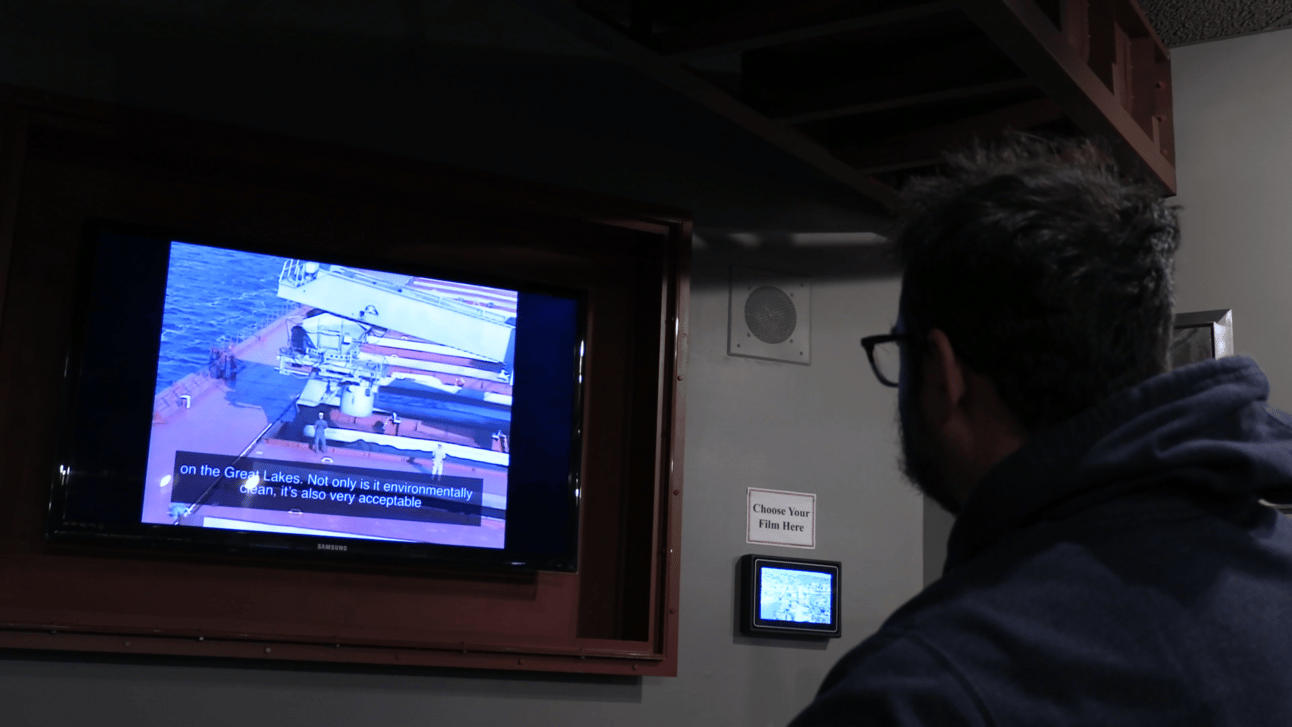

Visitors to the Lake Superior Maritime Museum can watch a dated video: “Low sulfur coal has become an increasingly important bulk cargo for the Twin Ports…Not only is it environmentally clean….”

While reading about Duluth’s history, I discovered that my great uncle Arthur Baum had published a lengthy profile of the city for the Saturday Evening Post. Baum’s Duluth profile was part of the Post’s “Cities of America” series, which ran from 1945 to 1952, presenting rich snapshots of the post-war economy in 120 North American cities. The series provides a strong sense of what scholars have called the “New Deal consensus,” when the political class largely agreed around the need for robust public investment, strong industrial policy, and support for labor unions and safety nets.

Many passages from Baum’s colorful portrait of the Duluth of 1949 resonate today, none more so than the ones that situate Duluth at the center of numerous, historic economic crises. Baum depicted a city constantly vacillating between economic booms and busts: “Duluth’s history is a long series of counter punches at circumstances and events. When Duluth wins a round, it habitually comes up off the canvas to do it.”

A representative figure in Duluth’s series of comebacks is that historic financier Jay Cooke, who selected the city as a crucial stop in his railroad empire. Cooke invested in building canals and grain elevators in Duluth, until the collapse of his banking house caused the Panic of 1873, also delaying Duluth’s incorporation. Historians have asserted that Cooke’s childhood as the son of an Erie Canal builder instilled in him a strong sense of economic optimism surrounding public works.

A statue honoring Duluth champion Jay Cooke, a banker best known for financially supporting the Union effort during the American Civil War. During the war, Cooke assured Americans that investing in Treasury bonds was “quite as efficient as a charge of bayonets.”

Baum characterized the widespread belief that the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway connecting the Twin Ports to the Atlantic Ocean would deliver economic salvation to Duluth. “Duluth yearns so passionately for a St. Lawrence Seaway,” Baum wrote, “that it has been called ‘an old maid city looking under its bed every night for an ocean.’”

These economic prognostications may not have been very realistic, but Duluth was not the only Midwestern city to place its trust heartily in them. The profile of Detroit that ran in the Post’s Cities of America series closed with a prediction that “Should the future open up to her the St. Lawrence Waterway, cut a few expressways through the barriers of international trade… the earth will tremble as [Detroit] rises from her hands and knees and begins to move mountains, three ranges at a time.”

Enamored with Lake Superior’s beauty and fascinated by the city's apparent dynamism, Sarah and I decided to move to Duluth in the spring of 2023. One factor in our decision was a sense of action by Minnesota’s state government. Minnesota’s legislature initiated its 2023 session with the passage of a 100% clean energy mandate, and I even got to see one of my IRA implementation ideas go into effect when I advised legislators on the creation of a new green bank.

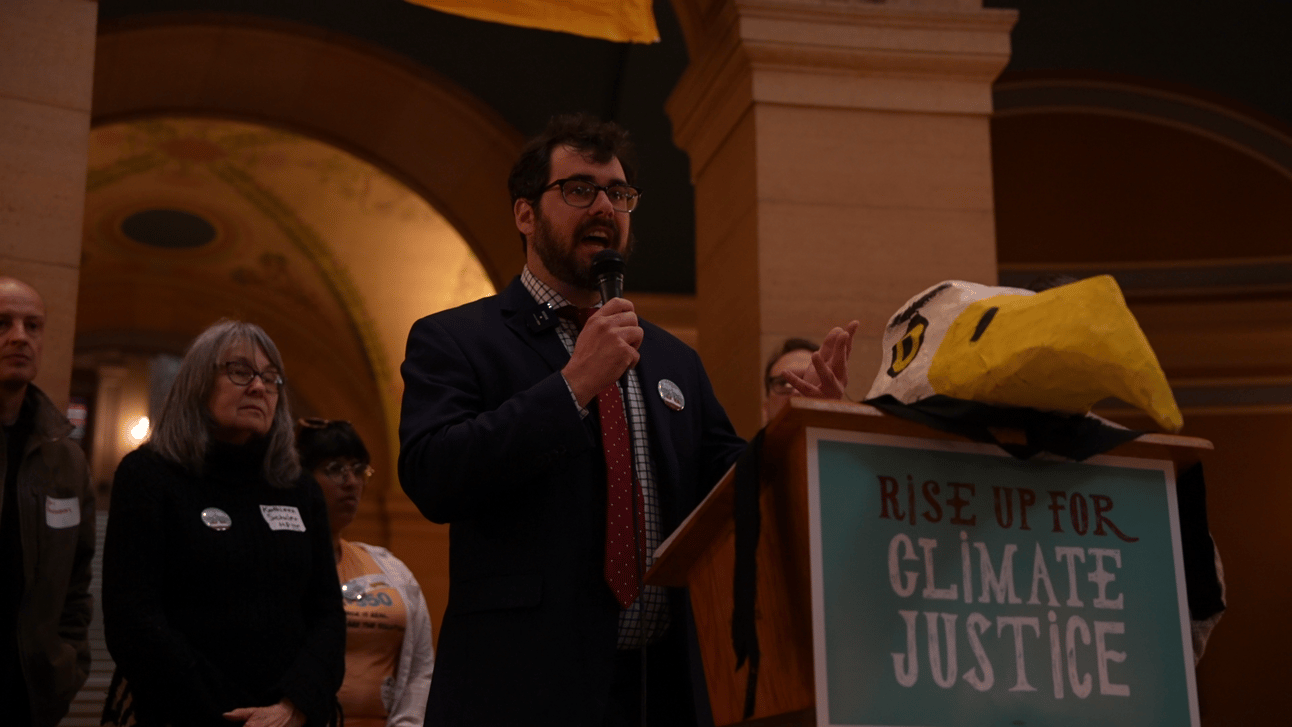

Speaking at a climate rally in Minnesota’s state capitol.

From US Steel to the Green New Deal

Primarily because of shipping, the names of prominent US Steel figures are still ubiquitous in Duluth. The William A. Irvin, an ore ship named for the former president of US Steel, is now a tourist attraction. You can head down to the docks in west Duluth and sometimes see the Edwin H. Gott, named for a former CEO of US Steel. You can visit Glensheen mansion and tour the estate of mining magnate Chester Congdon, whose company was absorbed when JP Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie arranged the megamerger that made US Steel the first ever billion dollar corporation. Or you can drive around the blighted western Duluth neighborhood of Morgan Park, named after Morgan when it was first built as a company town in 1915. Further west, there is the neighborhood of Gary, named for US Steel co-founder Elbert Gary, just like Gary, Indiana— another Great Lakes steel town hit hard by industrial decline in the latter half of the last century.

The names of 20th century steel titans still appear on the hull of most Great Lakes ships, despite waves of consolidation and financialization that re-shaped the steel business at the end of the century. The Joseph L. Block and the Stewart J. Cort are named for men who once led giant steel producers, though the companies they ran are now defunct. It is dizzying to read through the corporate shuffle of names and acronyms to determine where their assets ended up. The John G. Munson is named for the man who once oversaw US Steel’s Great Lakes shipping fleet, though the fleet was sold off and is today a subsidiary of the Canadian National Railway Company.

US Steel hasn’t had a physical presence in Duluth since 1987, when the company closed down the steel mill in Morgan Park. Still, it is through Duluth that US Steel projects its influence throughout the Great Lakes region. And so over the last few years, stories about US Steel’s prospective sale have made headlines in Duluth’s paper of record. At first, US Steel seemed likely to be sold to Cleveland-Cliffs, a steel manufacturer that operates four of the Iron Range’s remaining mines.

This sale would have brought all eight of the primary domestic steel producers experimenting with cleaner hydrogen production under the same company’s control. But US Steel executives rejected Cleveland-Cliffs’ offer in favor of a $14.9 billion sale to the Japanese company Nippon Steel, which has announced plans to invest in the existing blast furnace at Gary Steel Works, extending by 20 years the life of the nation’s most polluting steel plant.

For all of Arthur Baum’s descriptions of how Duluth’s importance to wartime production led its population to flourish, his piece failed to foresee the long, slow period of deindustrialization that loomed around the corner. In the 1970s and 1980s, the New Deal consensus began to fray. Those commitments to infrastructure, public investment, and unionization weakened, giving way to a dominant American business culture that worshiped short-term profits for shareholders. This period again found Duluth at the whims of economic booms and busts, with the most epic bust of all cresting in the 1980s, when the closure of numerous plants and mills prompted the exodus of thousands of residents.

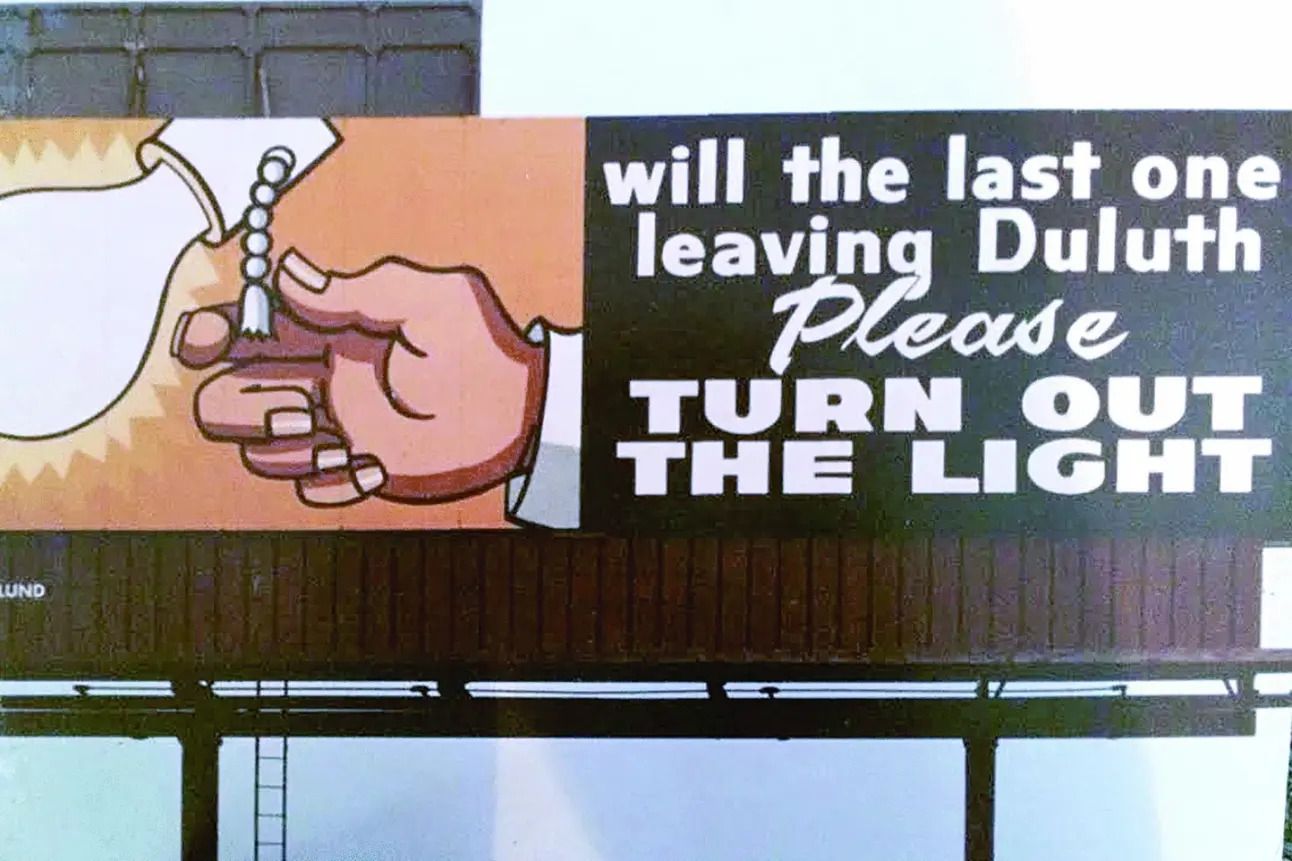

Things got so bad that a billboard along I-35 read “Will the last one leaving Duluth please turn out the light?” Nearly every climate haven news story recounts this anecdote, perhaps as a way of suggesting that a PR campaign founded on “climate proofness” might be a means of luring people back to depopulated cities like Duluth. In 1974, Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale had come to downtown Duluth to give a speech promoting the revitalization of the domestic shipbuilding industry. When his Senate bill to achieve that goal fell through, it was the latest in a series of setbacks for beleaguered American shipbuilders. During his presidential campaign a decade later, Mondale coined the term “rust belt,” and it stuck as a descriptor of what had happened to many Midwestern towns in the 1980s.

Understanding this painful history makes it possible to understand why, when it comes to Duluth and steel, the city’s wounded pride matters. Commentators on a New York Times podcast were baffled as to why President Biden cited national security concerns in attempting to block the sale of US Steel to an ally, but the reasons are pretty straightforward. For Duluth and other working class towns throughout the Rust Belt, the symbolism of US Steel getting bought out by a company with a name that translates to Japan Steel carries quite a psychic blow.

During Biden’s presidency, Rust Belt cities like Duluth were starting to see the benefits of his renewed attention to industrial policy. When the lake freighter Mark W. Barker emerged from Cleveland’s harbor in 2022, it was the first time that a new American-made ship had launched since the dreary 1980s heyday of deindustrialization. Massive wind turbine blades lined the railroad tracks leading to Duluth’s marine terminal. A university research lab near Duluth received a $2.9 million grant to research green steel as part of a Department of Energy (DOE) program supporting decarbonization projects. Duluth was awarded another DOE grant to experiment with a geothermal project that might make the city the first to develop a carbon-free heating system through a creative use of wastewater.

Wind turbine blades line the railroad tracks near the “Point of Rocks,” a geographic and political point of delineation between east and west Duluth.

My own contribution to this policy shift had been to work on a congressional proposal for a National Investment Authority, inspired by the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC). At the height of the Great Depression, Congress created the RFC to steer public investments in failing banks, while also supporting the economy through disaster relief and investments in agriculture, housing, and much more.

President Roosevelt expanded the scope and scale of the RFC, making it a core part of conducting industrial policy and shaping the New Deal. The RFC was instrumental first in formulating New Deal power policy and eventually in fighting World War II. In the first chapter of his memoirs, RFC director Jesse Jones describes the moment when Congress greatly expanded the RFC’s powers to mobilize the country for war: “We began our preparedness program by making contracts to purchase for stockpiling purpose all the tin and rubber available to an American buyer anywhere on earth.”

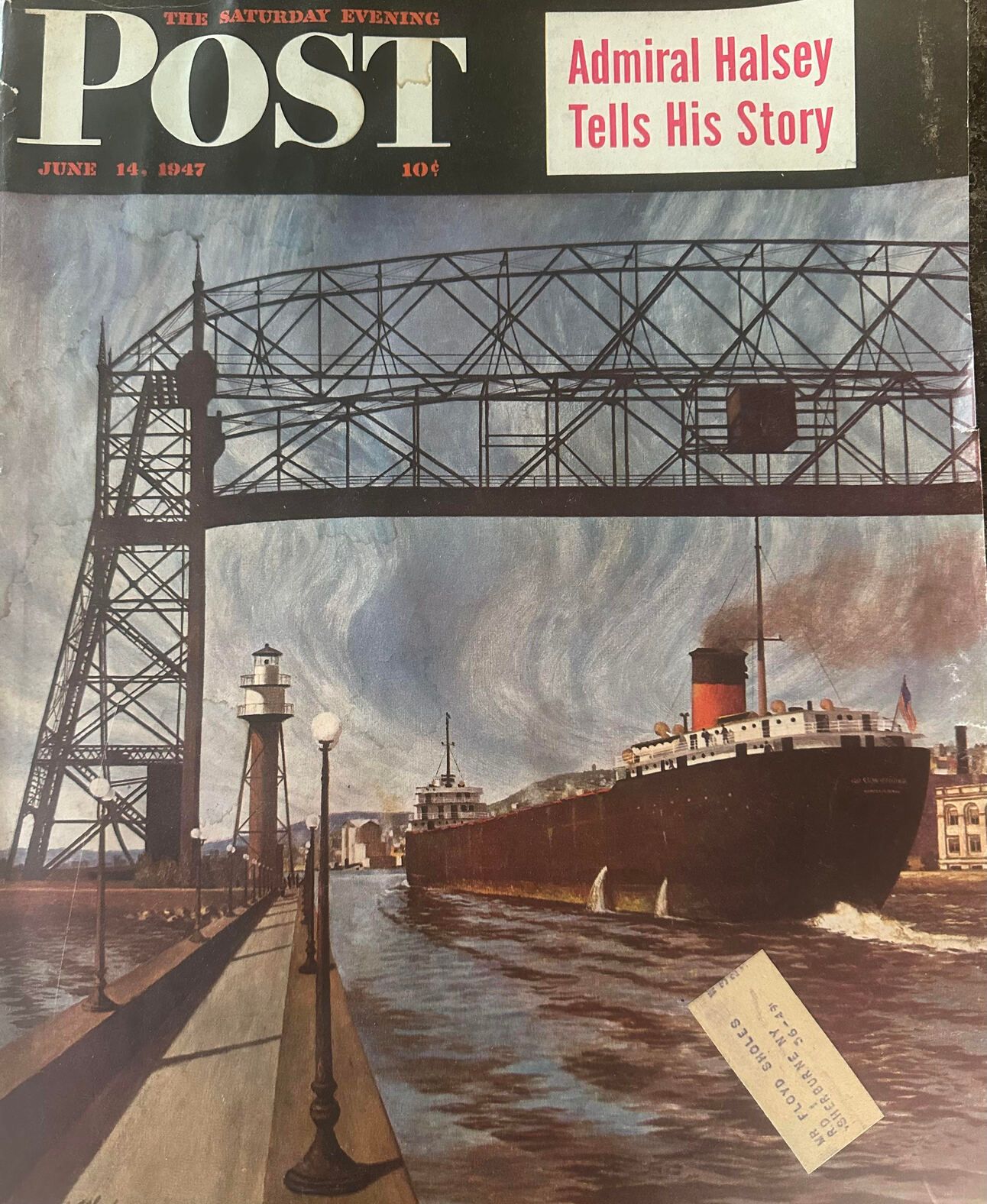

Duluth’s Lift Bridge on the cover of a June 1947 edition of the Saturday Evening Post. The same edition features a profile of Buffalo by RFC chronicler Edward Angly.

In a short period of time, the RFC stood up many industrial plants, including the nation’s first synthetic rubber manufacturer. Meanwhile, consumer loans and rural electrification grants from the RFC contributed to the modernization of American farms, and the RFC financed aluminum plants to ramp up military production. Access to low-cost electricity arranged by New Deal power policy was a key reason why the Manhattan Project located its nuclear processing labs in Tennessee and Washington.

The American economy was transformed by the RFC’s activities, as were so many of the cities that the Post would profile after the war. Duluth was no exception, since Great Lakes iron ore shipping was called the “jugular vein” of wartime production needs. Incidentally, Jones wrote his memoirs with journalist Edward Angly, whose profile of Buffalo ran in the 1947 edition of the Saturday Evening Post on which Duluth’s Lift Bridge graced the cover.

Biden was right to try to bring climate and industrial policy together. Addressing the climate crisis necessitates economic transformation on the scale of what it took to fight the Great Depression and fascism during World War II.

To be concluded in Part Two.

This unique essay is made available for free to the public thanks to our paid subscribers. Join their ranks today and grow the movement:

Reply